Georgia O'Keeffe and her paintings

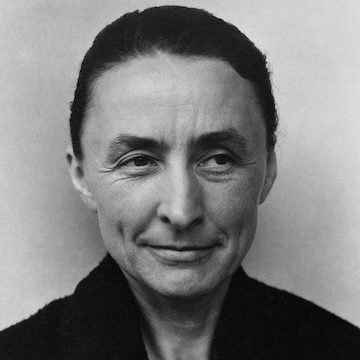

One of the first female painters to achieve worldwide acclaim from critics and the general public, Georgia O'Keeffe was an American painter who created innovative impressionist images

that challenged perceptions and evolved constantly throughout her career.

After studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago she attended the Art Students League in New York, studying under William Merritt Chase. Though she impressed the league with her oil

painting "Dead Rabbit with Copper Pot," she lacked self-confidence and decided to pursue a career as a commercial artist and later as a teacher and then head of the art department at West Texas

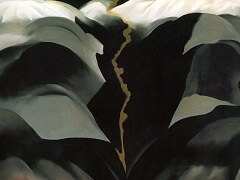

A&M University. At that time she became acquainted with a landscape that would become iconic within her work, the Palo Duro Canyon.

O'Keeffe did not stop producing charcoal drawings and watercolors during her hiatus, some of which were seen by Alfred Stieglitz, her future husband. Stieglitz was a successful photographer

and modern art promoter who owned the 291 Gallery in New York City. He was struck by the sincerity within her work and organized her first solo show in 2017, composed of oil paintings and

watercolors completed in Texas.

After their marriage, O'Keeffe became part of an inner circle of American modernist painters who frequently showed in Stieglitz's gallery. Many of the works produced by Georgia O'Keeffe during the

1920s and 1930s hover enticingly on the margins between figuration and abstraction. The notion that car could be entirely non-representational, or abstract, was widely explored in the decade from 1910,

particularly in the works of the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky and the Dutchman Piet Mondrian. O'Keeffe's

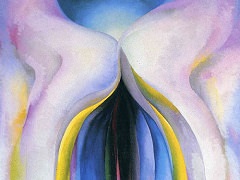

works shifted towards oil paintings which appeared to be magnified natural forms. In 1925, her first large-scale flower painting was exhibited in New York City. Petunia

marked the beginning of a period of exploration on the flower theme that would continue throughout her career. By magnifying her subject, she emphasized shape and color and brought attention to the

tiny details within the flower.

During her life, the flower is a motif that Georgia O'Keeffe always returns to, as artists have always returned to their beloved themes - Van Gogh his

Sunflowers, Monet his Water Lilies, and

Rembrandt his self portrait.

O'Keeffe's painting's subjects caught the attention of collectors and critics who responded with alacrity. Their discussion of the O'Keeffe's works were often colored by the popularized tenets of

Sigmund Freud, which by the 1920s were widespread in America. In a cultural atmosphere initially titillated and gradually transformed by his theories, art and its

critical reception - like many other aspects of modern life - where invariably, and indelibly colored by Freudian consideration. Many claims that the images which Georgia O'Keeffe created when painting flowers,

was work which was highly sexual, and many went as far as to say it was an erotic art form; but O'Keeffe rejected that theory consistently. In an attempt to move the attention of her critics away from their

Freudian interpretations of her work, she began to paint in a more representational style.

In her series on New York, O'Keeffe excelled in painting architectural structures as highly realistic and expertly employed the style of Precisionism within her work.

"Radiator Building-Night, New York" from 1927 can also be interpreted as a double portrait of Steiglitz and O'Keeffe. Object portraiture of this kind was popular amongst the Steiglitz circle

at the time and greatly influenced by the poetry of Gertrude Stein.

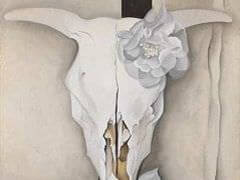

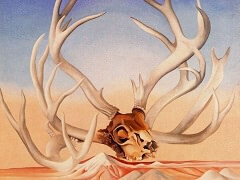

In 1929, seeking solitude and an escape from a crowd that perhaps felt artistically and socially oppressive, O'Keeffe traveled to New Mexico and began an inspirational love affair with the

visual scenery of the state. For 20 years she spent part of every year working in New Mexico, becoming increasingly interested in the forms of animal skulls and the southwest landscapes.

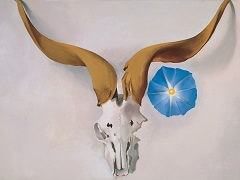

While her popularity continued to grow, O'Keeffe increasingly sought solace in New Mexico. Her painting Ram's Head with Hollyhock encapsulates so much

novelty while still maintaining with her classic aesthetic of magnifying and showing the beauty in small, natural details. While her interest in the southwest increased, so did the value of her

paintings in the New York galleries.

She was featured in two one-woman retrospectives at the Art Institute of Chicago and The Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan in the 40's, becoming the first woman to ever have a retrospective at the latter. She developed an obsessive interest in formations of rock near her home in New Mexico and spent hours painting in the sun and wind.

In 1946 O'Keeffe's husband Stieglitz suffered a cerebral thrombosis and she moved back to New York for three years after his death to settle his estate before permanently settling in New Mexico.

With the loss of Stieglitz came the lessening of her public exposure. O'Keeffe became once again interested in architectural forms, this time focusing on details like her patio wall and door.

Her 1958 painting Ladder to the Moon marked yet another shift in her work which many interpreted as a self-portrait that depicted the transitory nature

of her life. Others viewed it as a religious statement that showed a link between the earth and cosmic forces above it.

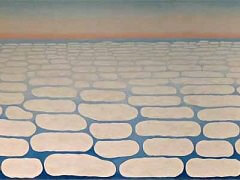

Adding onto a history of abstraction, in the early 1960s O'Keeffe painted an extensive collection of aerial cloudscapes inspired from her view from the windows of airplanes. In 1970 the

Whitney Museum of American Art began the first retrospective career of her work in New York since 1946 which greatly revived her career.

Though her eyesight became compromised in the 1970s, she continued working in pencil and charcoal until 1984 and also produced clay pots and a watercolor series. In 1986 she died at her home in

Santa Fe, New Mexico and requested her ashes be scattered over the top of Pedernal Mountain.

While her work varied between the literal portraits, abstractions and landscapes, O'Keeffe's work is still most identified by her iconic flower paintings. In 2014 the Georgia O'Keefe Museum sold

a floral painting for $44 million dollars at auction setting the record for artwork sold by a female artist. The piece, titled Jimson Weed/White Flower No.1

was painted in 1932 and is an iconic representation of a large-scale flower.

Georgia O'Keeffe died in 1986, at the age of ninety-nine. In her lifetime, she received unprecedented critical acclaim. She was elected to the National Institute of Arts & Letters, the American

Academy of Arts & Letters, and received the United States Medal of Freedom. In 1946, she was the first woman honored with a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, and, twenty-five years later,

the Whitney Museum's retrospective of this "Mighty Mother's" work garnered her renewed critical acclaim and an ardent feminist following. Following her death, a large portion of her estate's assets was

transferred to the Georgia O'Keefe Foundation. Later when this foundation dissolved the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum was established in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Assets

from her estate included an immense body of work and archived materials. Her home in New Mexico was designated a National Historic Landmark is also owned by the O'Keeffe museum.

Within her work and life, O'Keeffe was unapologetically true to her own vision. When she did attempt to supersede her intuition to complete hired work, she became troubled and always retreated back to what felt

familiar and natural. She remains one of the most important and innovative artists of the twentieth century.